An interview with Valeria Khripatch

Valeria Khripatch is a largely self-taught artist, whose practice includes dancing, choreographing, and curating. Originally from Belarus, the France-based performer explores themes, such as embodied and collective memory, migration, and the subconscious. As she notes on Instagram, their artistic research moves “between risk and irony”. As part of the Empowering Creative Minds project, Douri asbl invited Khripatch for an interview to speak about dancing, improvisation, and the precarity of artists.

Douri: What key milestones have shaped your creative journey from the beginning until now?

Valeria Khripatch: I have been dancing since childhood, but at first, I didn’t feel confident enough to pursue choreography as a profession. Instead, I graduated from the Belarusian State Economic University. I worked for six years in an office in the oil and gas sector, where I found ways to sublimate my creativity through import, logistics, and communication. After those years, I realized that this was not my true path. I left the corporate world and fully committed to contemporary dance.

Since then, my journey has been complex and multifaceted. I have shifted between roles as a dancer, teacher, choreographer, director, and manager, carefully gathering experience across diverse projects and contexts. For example, I worked extensively as a tutor with architecture students, took part in inclusive artistic projects as a dancer, curator, and choreographer, organized morning raves filled with music and improvisation, led creative laboratories for amateurs, and created choreography for both theater actors and dancers. I have performed in large-scale dance pieces with up to 30 participants in experimental site-specific projects, acted in films, and joined multinational, cross-disciplinary artistic residencies.

In what ways have your upbringing and personal experiences influenced your artistic direction?

A descriptive word for my background is collage. For me, my childhood and personal experiences are a kind of collage — not created on paper or in graphics, but diffused in the air like essential oil. Since childhood, I often felt shy about what I would call my “quirky” side, and I tried to hide it. Only through creativity and choreography — and especially once I decided to fully commit to this profession — have I been learning to embrace and integrate that part of myself instead of concealing it.

Have you found that challenging experiences — whether personal or societal — have impacted your creative process or influenced your artistic path?

Yes, absolutely. All the challenging choices I have made — from leaving a stable office job for an unpredictable freelance artistic career to experiencing two migrations within the last three years — have deeply influenced my path. These transitions taught me to adapt, to stay flexible, and to find creative ways of building new connections and projects in unfamiliar environments. They pushed me to see change not only as a difficulty but also as a source of artistic energy and growth.

How has your creative practice helped you process or move through difficult experiences?

It’s not an easy question to answer. In the moments when I felt very low, dance helped me release emotions and stop overthinking my difficulties. Through the precarity and instability of the artistic profession, I also learned flexibility: to let challenges rest when no solution is clear, and to return with a fresh perspective.

In general, being an artist means constantly seeking balance between the childlike and adult sides within me — staying curious, reflecting, inventing new ways of creating, and choosing when to be visible or when to consciously embrace invisibility.

Do you believe that art can express emotions and experiences that are hard to articulate in words?

Yes, I deeply believe in it. There was a moment when I doubted the necessity of the choreographic pieces I was creating and choreography in general. Then one wise person reminded me: art may not be in the very first row of human needs, but it is definitely in the second. Art helps us to feel, to dive into fantasies and illusions, and to develop our imagination and emotional intelligence.

This dimension of our existence is essential. Feelings support our intellect, and intellect supports our feelings — and art is one of the spaces where the two can truly meet.

Has your approach to expressing painful or difficult experiences changed over time — if so, how has that evolution taken shape?

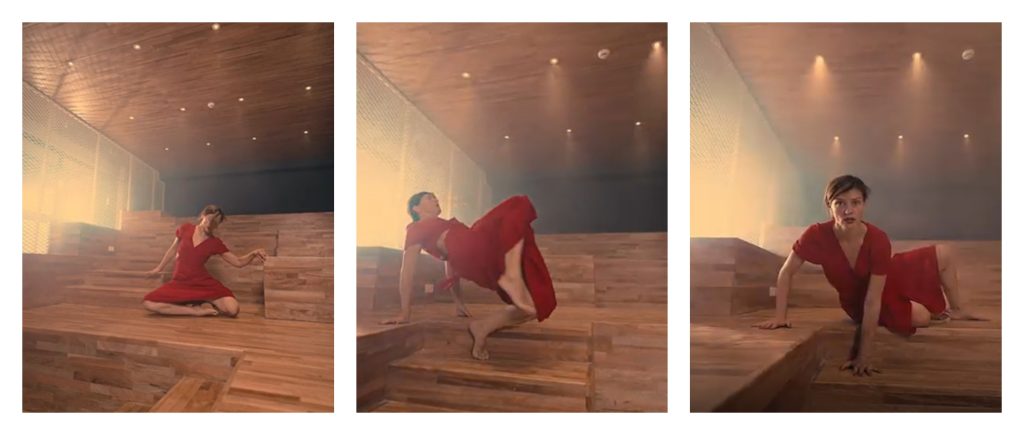

When I first began creating small performances, it felt like a way of building dialogue with the audience. That’s why I was drawn to immersive and site-specific projects, where the fourth wall disappears and the distance between artist and viewer dissolves.

Over time, I realized it is impossible to exclude personal experiences from artistic practice. But I am not interested in dwelling on pain — I want to transform it: to give shape to the “creatures” of our subconscious, to tell stories through the body, and also to use irony instead of drama.

How do you interpret the term “vulnerable artist” in the context of your own practice?

To me, being a vulnerable artist means staying sincere, facing precarity every day, and not losing yourself in the desire to be seen or noticed by the outside world.

What role have collaboration and partnerships played in your artistic journey?

Collaboration is not always easy, but it is always enriching. In the past five years, I’ve often worked in duets with other choreographers, learning to balance visions and merge different approaches into one project.

I especially value interdisciplinary collaborations — with musicians, visual artists, fashion designers, or architects, whose sense of space deeply inspires me. Working with objects and environments often becomes a starting point for new ideas. For me, collaborations open perspectives and let me see the world through other eyes.

What does it mean to you when your art resonates with or impacts others?

This is a delicate question, and I think it depends on the context. When I work with amateurs — for whom dance is a form of self-expression alongside other professional activities — I focus on creating a dialogue, developing a shared choreographic language, and helping them open up and become bolder. I feel happy if I can achieve even a little of that.

In professional projects, I try to focus first on what genuinely interests me. When the work resonates with viewers, it’s invaluable, but the main priority is staying honest to my own curiosity and artistic exploration.

How do you see the role of institutions — such as theatres, publishers, galleries, or museums in shaping the landscape of art and creativity?

Institutions are essential as mediators and translators, as sources of information about art. They serve as a bridge between the artist and the audience, while also shaping the cultural context in which artistic practices are understood and valued.

Do you think being part of these circles affects how artists view the value of their own work or their place in the field?

Yes, I think it does affect how artists view the value of their work and their place in the field. But I also believe it should go both ways: artists bring their vision, and institutions help to frame it. Ideally, it is a dialogue — or at least, it should be. Risks appear when institutions dominate this dialogue too strongly, shaping not only how the work is received but also how the artist perceives their own value.

Would you consider choosing to engage with or step away from these institutions a personal decision? What impact might this have on artists who haven’t had access to such opportunities?

It’s a matter of balance, circumstances, and of course personal choices. At one point, I realized that staying completely alone in my practice is very complicated. In order to develop and enrich your artistic work, you need dialogue with the outside world, exchange with others, and ideally to find your people — to create your own team, which in a way already becomes a kind of institution. But, of course, this is subjective.

What types of support do you consider essential for sustaining your artistic practice and expanding your social engagement?

For me, the most essential support is time, space, and continuity. Access to rehearsal studios, financial stability through grants or stipends, and opportunities for long-term projects are crucial for sustaining artistic work. Equally important is being part of an engaged community — having people to exchange with, to challenge ideas, and to create together. This kind of network not only supports artistic growth, but also makes social engagement more natural and impactful. It's generally evident things.

Have you faced difficulties in accessing the support you need?

Yes, of course — like many other artists, I have faced such difficulties. I have already gone through two migrations, and each time I had to start from the very beginning: without knowing anyone, searching for information, instinctively looking for “my people” and places that appreciate and share my vision. At the same time, you realize that there are many artists around you, and there is no guarantee of success.

In general, the barriers migrating artists face can be even higher — from language and financial limitations to a lack of access to networks or institutional support. These factors often make it harder not only to sustain artistic practice but also to feel that your voice has a place in the wider artistic landscape.

Do you have any messages or recommendations you'd like to share with organizations or institutions that support the arts?

Frankly, I’m not sure. I definitely understand how complicated it is for institutions to make their choices, and that these decisions are always subjective. Of course, I would appreciate receiving more specific feedback on why I wasn’t selected for a residency or project. It helps to reflect, move forward, and develop, rather than give up. But I realize this might be utopian, considering how many applications institutions receive.

Do you incorporate practices like meditation or other reflective tools into your creative process?

For me, dance itself is a form of meditation in action — it helps me stay fully present. It’s like skiing or surfing: if your mind is elsewhere, you immediately lose balance and fall. I also enjoy working with automatic writing to bring images and ideas from the subconscious without blocking myself with reasoning or logic.

In improvisation, it’s important for me to provide a point of reference — a small framework to start from — while still allowing freedom for personal interpretation in the realization of the proposed idea.

What techniques or tools have you found most effective in exploring complex experiences through your art? Are there any you'd be willing to share or teach — whether to fellow artists or the public?

One of my key tools to wake up my imagination is text. I collect quotes from books or interviews and write short texts, which I call the “poetics of everyday life.” This practice grows out of simple observation — the art of paying attention.

I also use drawing, not for technical skill but as a way to spark ideas. In improvisation, I often start from objects — clothing, books, tables — that offer both limitations and possibilities. These tools are intuitive rather than systematic, but I would be glad to share them with others, whether fellow artists or the public.

Are there specific workshops or resources you think should be highlighted to help others develop and refine these techniques?

As I mentioned before, my artistic approach is a collage of different experiences, and I am largely self-taught. I have developed and am still developing my skills through various circumstances and opportunities, so it’s difficult to point to exact workshops or resources. I believe the most important resource is exchange, and the best way to gain this experience is through participation in multidisciplinary residencies or collaborative projects.

How do you view the role of technology and social media in sharing your work and expanding engagement with the issues you explore?

At the moment, I feel some stress about the necessity of using social media. I’m not sure it truly helps me share my vision, and I often feel tired from the sheer amount of information I receive through these platforms. I think this feeling might be temporary. I’m not very experienced with new technologies, and I know there is still a lot to explore. Perhaps science and technology could become more interesting tools for me in the future, but this is something I’m still discovering.

Are there any current or upcoming projects you’re excited about?

I’m currently working on several small projects, and I’m also exploring two broader research topics. One is age — memory and the experience of aging — and the other is communication, especially how the body can act as a language. These themes are still in a research phase, but I’m excited about where they might lead and how they could shape future works.

Thank you Valeria Khripatch for this interview.

Conducted as part of the Empowering Creative Mindsproject, this interview offers just a glimpse into Valeria’s world.

You can learn more by visiting her website: https://lightness.tilda.ws//projects_en

The Empowering Creative Minds project is funded by the EU Creative Europe Programme, supporting cross-cultural collaboration and artistic growth across Europe.