An interview with UNO

Prepared by: Douri’s Empowering Creative Minds team

Edited by: Jang Kapgen

Uyi Nosa-Odia, known as UNO, is a Luxembourgish-Nigerian curator and painter specialized in Afrocentric contemporary art. His cultural heritage as well as personal history shape his artistic approach – reflected in over 150 professional artworks, from contemporary portraits to more abstract paintings. While he paints foremost for himself , he explains "collaboration has been a lifeline" throughout his artistic career. As part of the Empowering Creative Minds project, Douri asbl spoke to UNO about family, Western audiences, and the role of institutions. As he says, "if you want diversity, support the roots, not just the flowers."

Douri: What key milestones have shaped your creative journey?

UNO: My creative path has been marked by quiet transformations and bold leaps. One turning point was discovering how traditional African techniques, like those used by juju priests, could be reimagined on large canvases. That was how the painting series The Juju People came to life. It’s a story of identity, history and family. Another milestone was building my own family and home while reconnecting with my roots after years of distance. I can’t be alone anymore. I have a child now. Each life event finds its way into my art. In many ways, the bottles I use to create my artwork have learned to speak before I can find the words.

How have your upbringing and personal experiences influenced your art?

I grew up around symbols, real ones. Not just visual, but lived. My childhood in Benin City was rich with rituals, stories, and a spiritual language that most textbooks can’t decode. That upbringing embedded in me a kind of visual memory I still draw from. When I moved to Europe, that memory didn’t fade – it began to speak louder, and I’ve spent years learning how to let it speak clearly through my work.

Have challenging experiences shaped your creative path?

Absolutely. Grief, disconnection, migration, all these things reshaped my understanding of self. I lost my eldest brother. I spent nearly a decade apart from family. I lived in-between cultures, longing and rebuilding. But pain has a way of carving out deeper spaces in the soul. And in those spaces, I found that the language of art stays true, one of color, contrast, and depth. One of solace too.

Has your creative practice helped you through hard times?

Yes, painting became both a mirror and medicine. It allowed me to sit with things I couldn’t explain: loss, pain, doubt, identity, and work them out with my hands. I don’t just create to produce art; I create to stay human.

Can art express what words can’t?

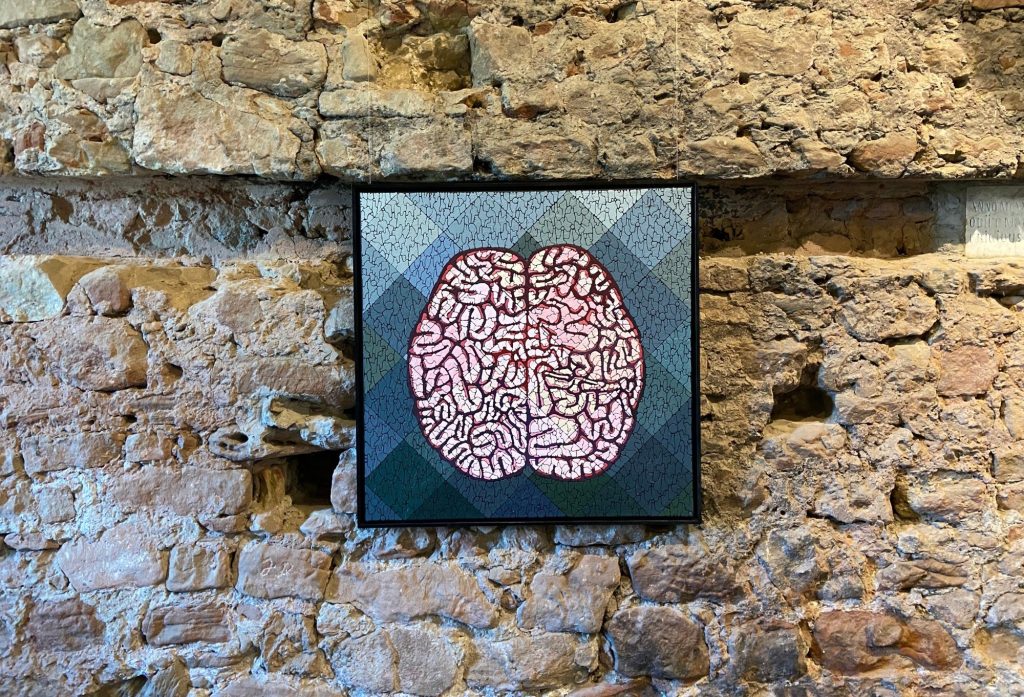

Without a doubt. There are emotions so layered, so ancient, that language doesn’t do them justice. The painting, Uhun (the Head Deity), from 2022 and part of The Juju People series, is a good example. But when I paint a face, a mask, or even a shadow, it speaks. Sometimes clearer than I ever could in words.

What are the challenges of expressing personal or traumatic experiences in art?

One challenge is the vulnerability – it’s like bleeding in public. Another is the risk of being misunderstood. Sometimes people see the aesthetics, but miss the ache behind the thick lines of colours. Or worse, they exoticise the pain. It’s a delicate dance between exposure and self-preservation.

Has your way of expressing difficulty evolved?

Yes, it’s matured. Early on, I hid behind generalism. Now, I don’t flinch as much. I’ve learned to trust the honesty of dark tones, raw texture, and silence. The evolution wasn’t as much technical, it was emotional.

What does being a "vulnerable artist" mean to you?

It means I’m willing to bring my whole self to the canvas, even the parts I wish weren’t there. Vulnerability isn’t a performance; it’s a decision to stay present, open, and sincere in the face of a world that often rewards masks.

What role has collaboration played in your work?

Collaboration has been a lifeline. Working with cultural groups, social organisations, galleries or even other artists, like in the Tableaux de Fusion project for Esch2022, adds new dimensions to my practice. It reminds me that my story is part of a larger chorus.

How has community connection (or lack thereof) influenced your work?

For years, I was cut off from my community. That absence taught me to yearn, and that yearning made its way into my art. Now that I’m rebuilding those ties, my work has become more grounded, more generous, and more communal.

What does it mean when your art resonates with others?

It’s deeply humbling. When someone sees a piece and says, "this relates to me", I know the work has done its job. I don’t create for people’s approval, but I hope to reach them. Resonance is the reward of truth well told.

How does cultural or societal context affect your work’s reception?

It shapes everything. African imagery doesn’t always translate easily in Western settings, but that’s okay. Sometimes the misunderstanding sparks curiosity, and that’s where dialogue begins.

What role do institutions play in shaping art?

They can amplify voices, or silence them. When institutions are inclusive, they help us dream bigger. When they’re gatekeepers, they shrink the field. My hope is that they always choose courage over caution.

Do institutions affect how artists value their work?

Yes, they can. Validation is a powerful drug. But I’ve learned to hold my value internally. Institutions are platforms, not gods.

Is choosing to engage with institutions a personal choice?

Very much so. For some, it’s strategic. For others, it’s about survival. For me, it’s about alignment. My project, Ugegraff, hosted at the Museum of Resistance and Human Rights from September to December 2025, paints a perfect picture of such alignment. I won’t step into spaces that ask me to water down my truth. That choice comes with risks, but also integrity.

What support is essential for sustaining your practice?

Time, space, and trust. I need the freedom to experiment without fear of failure. I also need networks that understand that art is a slow fire, it doesn’t always burn bright, but it warms the world eventually.

What kind of institutional support would help?

Long-term support. Not just one-off shows or symbolic funding. Real commitment: residencies, studio space, visibility, and resources that support the artist, not just the artwork.

Have you faced difficulty accessing support?

Yes. There are unspoken barriers: language, networks, and cultural codes. Sometimes I feel like I have had to work harder to arrive at this place. On the one hand, the challenges have made the journey more interesting. But on the other hand, it leaves a mark – mental and physical. That’s the reality.

What message do you have for arts organisations?

If you want diversity, support the roots, not just the flowers. Invest in the uncomfortable, the unfamiliar, the revolutionary. That’s where real culture grows.

Do you use meditation or reflective tools?

Yes, I do. Silence is a tool. So are walks, rituals, and sometimes just staring at the canvas until it stares back. Reflection is part of the art, it sharpens intention.

What techniques help you explore complex experiences?

Pouring. Layering. Controlled and uncontrolled. Texture. strong colours. And aggregation – aggregating certain shapes, lines, or symbols until they tell me what they mean. I’d love to share these methods in workshops, especially for young or emerging artists.

What resources or workshops would you highlight?

Workshops that blend personal history with artistic skill. Anything that helps artists connect their story to their craft. Safe spaces where we can explore pain and beauty at the same time.

How do you view tech and social media?

They’re tools, powerful ones. I use them to archive, connect, and reach new audiences. But they can’t replace presence. My art lives best in real homes, public halls, with real people, breathing the same air. Living.

What are your future aspirations?

I want to go bigger, public art, installations, more engaging and enriching. More collaborations and partnerships. I want my projects and art to grow across borders. And I want to keep telling the stories that matter, even when they’re hard. Especially when they’re hard.

Thank you Uyi Nosa-Odiafor this interview.

Conducted as part of the Empowering Creative Minds project, this interview offers just a glimpse into UNO’s world. You can learn more by visiting his website: www.artbyuno.com

The Empowering Creative Minds project is funded by the EU Creative Europe Programme, supporting cross-cultural collaboration and artistic growth across Europe.